and What One Can Learn from the Other

On a recent flight I sat behind a dad flying solo with three daughters, a comparative rarity from which it was hard to look away. The eldest in the window seat used earbuds to defend her personal space. The baby squirmed on the father’s lap. The middle child spent most of the flight watching construction of an elaborate cake on the Food Network, whisk attachment sending up billows of whipped cream, offset spatula spreading batter across the whole of the child’s small screen. I wondered: why are dough and frosting sufficiently interesting to hold this girl’s attention the whole flight? Why would I—and apparently her father—consider this appropriate viewing material for a child? Maybe it distracted her from the poor quality of her in-flight food. Maybe anything would suffice as long as it kept her busy and allowed dad to mind that baby. On an airplane it is easy to see why the presence of somebody else’s baby and the quality of the food matter to everyone. Back on solid ground, those two concerns might not seem so natural to treat together.

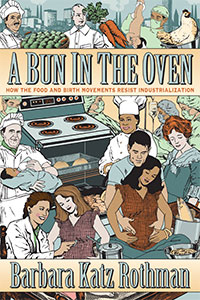

But Barbara Katz Rothman links the two issues and shows why we should care about them, beyond our own private intake and offspring, in her book, A Bun in the Oven: How the Food and Birth Movements Resist Industrialization (New York University Press, 2016). Rothman, distinguished sociologist at the City University of New York, has studied birth practices and advocated midwifery for decades—a movement she entered with her own home birth in 1973—and more recently became interested in the social context of food. Not just what we eat but where it comes from, how it is processed and sold, how it gets tagged with status markers, how small personal decisions about eating get made against the backdrop of manufacture. Her acuity is to put the two issues together, to diagnose problems in both areas as stemming from the same source: industrialization. Eating and birthing, she argues, are important features of life to which violence has been done by standardization, factory processing, profit-seeking—and in which industrialization has gotten pushback from those striving to recover something better. In food, industrialization means crops developed for sameness and shelf stability rather than for flavor or nutrients, grown by methods that denigrate the skills of farmers and cooks, and processing that harms the environment and wastes nutrients. In birth, industrialization means pathologizing the female body, distorting normal variations of human experience, submitting women to hospital rules and machines, and devaluing the skill of midwives.

Rothman notices that “foodies” seem to be having more success than “birthies” and wonders what the latter might learn from the former. Put practically, how could strategies behind some achievements of the food movement—turning us away from Hamburger Helper and Burger King and toward the farmer’s market and the Food Network—be parlayed into paradigm shifts in the way normal births are done? A few food-movement features could be leveraged for “birthie” success, starting with the collaboration of different groups and their efforts to build awareness, what Rothman names “splashing together” and consciousness raising. Additionally significant is the strength of elites to change opinions. The trickle-down effect of raised tastes has made better food available. By popularizing fancier food, foodies also have cultivated esteem for some old production methods that require specialized skills, thereby elevating those who have this mastery.

Before considering how foodies’ strategies might be

appropriated, foodies themselves deserve a little puzzling over. Why did

upper-middle class Americans suddenly become more interested in food in the

flush years of the late twentieth century? Food so easily could have stayed

unglamorous, associated with drudgery and domesticity. A couple of factors came

together. People who did not have to be interested in cooking began to be

interested, with increased visibility of men as celebrity chefs and discerning

diners. We all eat—and when possible prefer to like what we eat—so getting

people to see a personal stake in food matters was not that hard. Interest in

food avoided mere piggishness by acquiring high moral valence.

Before considering how foodies’ strategies might be

appropriated, foodies themselves deserve a little puzzling over. Why did

upper-middle class Americans suddenly become more interested in food in the

flush years of the late twentieth century? Food so easily could have stayed

unglamorous, associated with drudgery and domesticity. A couple of factors came

together. People who did not have to be interested in cooking began to be

interested, with increased visibility of men as celebrity chefs and discerning

diners. We all eat—and when possible prefer to like what we eat—so getting

people to see a personal stake in food matters was not that hard. Interest in

food avoided mere piggishness by acquiring high moral valence.

This consciousness raising was abetted by some widely publicized books, like Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma (2007), David Kamp’s The United States of Arugula (2007), and Eric Schlosser’s Fast Food Nation (2012). Films like Super Size Me (2004), Food, Inc. (2008), and Fed Up (2014) helped turn a fad into a movement. Fine-food advocacy managed to hit bunch of right notes while (mostly) skirting pitfalls of self-righteousness. Not mere gluttons or epicures, serious people argued that eating well not only provides enjoyment but boosts health and longevity; it displays refinement, choosing what is choiceworthy; it shows concern for others, for ecology, for labor conditions, for the future of our planet.

All pitfalls have not been avoided. Health and enjoyment in food can work at cross-purposes. The moralizing of your dining pleasure can go awry in many ways. One could say the heightened attention to food simply swapped one kind of gluttony for another, excess exchanged for obsessive concern with delicacy. (Even delicacy has trouble beating back excess, as evidenced by quests for the perfect gourmet fried-chicken sandwich or matcha cream-filled donut.) The difficulty comes in linking one’s private sense that these choices are nicer with a conviction that those choices should sway the behavior of others too. Foodie concern for the earth and the growers is real, and some in the movement care intensely about these and act accordingly. But the reason that most people care about food goes little beyond the belly gods. They like to eat what tastes good. Concern for sustainability is secondary.

This mix of conscience and indulgence has never been easy to balance. A. O. Scott named the contradiction in a New York Times review of The United States of Arugula:

You can glimpse the anxieties and aspirations of a segment of the native bourgeoisie (boomers, yuppies, bobos, whatever) struggling with the burden of cultural hegemony, and struggling also toward a quintessentially American, defiantly utopian goal, namely the reconciliation of pleasure and virtue. It is not just that we want food to taste good and be good for us; we also, with increasing fervor, want it to be the vehicle and symbol of our goodness.

What Scott describes is not just an American problem. There is, though, a specifically American twang to the phenomenon: foodies looking longingly to the Olde Worlde to supply a tradition we lack—the Tuscan, the Catalan, the Provencal— while simultaneously burnishing nostalgia for our own agrarian past.

Ah, that agrarian past. This tension goes clear back to Thomas Jefferson, who bequeathed us this vision, the sage of Monticello importing French haute cuisine and varietals to the Virginia countryside while dubbing farmers the chosen people of God.

Irony ferments within foodies’ contrary loves, the matchmaking of muddy-boots authenticity—locally grown! artisan made!—with that industrial gleam of efficiency and choice. Consider the artisan. Everything gets labeled “artisan” now, bread, cheese, WheatThins (though the correct expression should be “artisanal,” made by the artisan). The Renaissance drew a hard line between the artisan, that mere craft worker, and the Artist, a genius. Our new respect for the well-made loaf blurs that line, the artisan now honored as the genius, the well-heeled willing to pay well for his mastery of crust and crumb. Elite enthusiasm for elevated peasant cuisine revived appreciation for such work of the hands. Some elite eaters even dabble in these arts themselves, perfecting sourdough, putting up occasional preserves. But that is not daily bread, which most of us still buy at the store.

Because who has time? Mechanization of all that domestic labor frees many to do other jobs, jobs that involve the head more than the hands and feet, jobs that pay better than many works of our hands and allow us to pay someone else to make better bread for us. Nobody forcibly took away our ability to crimp a pie crust or the leisure to do it often. We gave them up voluntarily to do other things. Some might even say they were delivered from this handiwork by industrial processes.

Because we do not all have to grow our own grain and bake our own bread (or, for that matter, weave our own fabric or sew our own clothes) we have time to do other things. This arrangement is not straightforwardly better. Something is lost, both for our bread and for us, when we no longer know how to leaven that lump in our own kitchens. Nevertheless, amnesia about why we once fell hard for canned soup and Rice-a-Roni makes current nostalgia for artisanal bread a little hollow-sounding. Furthermore, disgust for the industrial clangs in contradiction with our hot ardor for the sleek, high-tech automation in so many other areas of life—including the kitchen. How are we to fit together these loves, of the smart fridge that tracks expiration dates and orders groceries, and the carrots we prefer to buy with dirt still clinging to their roots? Okay Google, find an answer while you set the oven timer.

Trying to inspire one movement with the other, Rothman recognizes that the path to enlightenment has not been direct:

For both of these movements, one could say it is the best of times and it is the worst of times. It is the age of wisdom, it is the age of foolishness, it is the age of organic kale chips, it is the age of McDonald’s, it is the epoch of belief, it is the epoch of incredulity, it is the moment of the unattended water birth, it is the moment of the elective cesarean section, it is the season of light, it is the season of darkness, it is the time of the rising star of the master chef, it is the time of ubiquitous processed corn, it is the spring of hope, it is the winter of despair.

The food movement might be too complex and checkered in its accomplishments to provide clear inspiration to the birth movement. Still, some elements of that might be instructive for birthies. Foodies’ appeal to aesthetics, their collaboration across related causes, their success at expanding options and elevating tastes might be borrowed readily. But birthies have a much harder time raising consciousness.

The aesthetic appeal seems well suited for advocates of midwife-assisted birth. The appeal of personalized care at the birthing bed is not much less obvious than the appeal of the artisanal loaf. Like better food, better birthing care can be presented not just as a luxury for the few but a good for the many. Rothman reviews the excellent safety record of U.S. midwifery: data for normal births indicate that midwife deliveries are at least as safe, by some measures safer, than doctor-hospital ones. Making hospitals the default setting for births has invited unnecessary intervention. The high incidence of cesarean section, now used in about about a third of American births, is the most telling evidence of the trends that Rothman rues. Emergency treatment in hospitals is essential in some births. But where this is not needed, midwife births tend to be less costly. Better care at affordable costs sounds like a sustainable package.

Rothman encourages us to stop maligning this birth choice as a quirky preference of the wealthy, conceding, “It is so easy to make fun of the elitism in our movement.” She invites readers to follow a thought experiment. If every woman with over $200,000 in annual family income had a “planned, elective cesarean,” a woman with a $75,000 income who had a “lovely, natural, healthy birth” might feel cheated, even if all the data show the latter option is better. In contrast, “if every woman who made over $200,000 had a midwife and a backup midwife she’d chosen early in her pregnancy, met with regularly throughout, arrive at her home when she went into labor and stay with her until the baby was born,” how would the woman with a lower income feel about her choices “as she had to pack her bag and leave for the hospital in labor”? The birth movement could follow the food movement in persuading elites this care is desirable and hoping the preferences of other women might follow. Changing the tastes of some could swap what is now a culturally dominant option (hospital birth with epidural) with preference for something that could be better for many. Rothman seeks a move from “the medical monopoly over birth...where a woman is expected to joyfully receive the baby the doctor delivers to her from the gaping hole in her abdomen,” to “a world in which a baby grows slowly underneath its mother heart, is birthed in love and in a moment of strength and power.”

The artisanal appeal also applies. The midwife is the artisan of birth. Food analogies are useful again: we are not only thankful to the baker because she gives us more choices for sandwich-making, but because the baker’s skill is valuable and the baker’s bread is good. Helpfully, Rothman places emphasis not just on the birthing woman’s freedom of choice but on the skill a midwife brings. You call a midwife because you need a midwife, not just because you want a choice that identifies yourself as a kind of person who prefers a midwife.

Figuring out how to make personalized, hands-on, respectful care the norm for birth might be a way for birthies, like foodies, to resist industrialization. But is industrialization really the problem with birth? For food, it is somewhat clear how industrialization is the culprit, how “factory farming” harmed eating, and how this resistance movement could help recall something lost. With food, there was a “before” that many could recognize, after raw nature: your grandmother’s table or the table of someone else’s grandmother was a good that could be reclaimed. For birth, industrialization might be part of the problem but is less clearly so. More evidently what changed birth is a certain kind of scientific approach mediated through medicine. It is much more difficult to conjure up a “before” for birth or to generate wide interest in reclaiming it. Reclaiming birth from what is sometimes called the hospital-industrial complex is tricky, since medicine often appears on the side of safety. Birth before heavy-duty medicalization came preloaded with some negatives (pain and infection) along with its obvious life-changing significance; it was a predominantly female event and substantially private. Most of us cannot pull home birth from a usable past.

There was not much of a public way of talking about birth at all until the medicalized way of talking about birth. So there is no ready alternative popular model of birth to swap out for that labor-and-delivery model. This is the uphill task for what Rothman names consciousness raising. Birth matters to everybody, but very few people think about it unless they already have a stake, as care providers or as expectant parents. Certainly most people think much less frequently about birth than they do about food. Thinking about food every day makes sense, while thinking daily about birth seems like an eccentricity. Why care so much about birth when the whole point is to get that baby out? Who (else) really cares, as long as mother and baby make it through healthy? In conversation birth often moves too quickly from a topic on which one has no opinion to one quickly polemicized; either you have given no thought to how babies are born, or you choose a side decisively and defensively. Somebody else’s birth choice feels like it impugns mine. Your homebirth implies that my emergency c-section for a preterm infant with breathing issues was somehow to be mourned, and my defense of hospital care implies that your bathtub birth was, at best, a little flaky.

The problem for the birth movement is not just figuring out how to normalize gentler modes of birthing, but building some common regard for childbearing. Without that, one’s particular preference about delivery is only that, a private preference. The problem is not so much that birth has been industrialized, or that doctors are involved. The problem is having doctors involved too much, claiming authority to explain and oversee childbearing, rather than only providing services to remedy medical emergencies. A range of circumstances and conditions make families grateful to have able doctors at birth. Still, the explanatory authority belongs elsewhere, to culture, custom, women’s practice, perhaps to religion, and in large parts to midwifery.

Rothman recognizes that in some cases women and babies need care provided by doctors and hospitals, and they should have access to it. But, given the history of midwifery in the United States and its intentional suppression by obstetrics through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, patients should not expect seamless collaboration between the two specialties. In Rothman’s model, if you have a normal pregnancy, you should pick a midwife; if you pick a doctor, even one who shares a practice with nurse-midwives, what you will get is an obstetric kind of care. If you pay that piper, he’ll call the tune, and American women have been paying that particular piper so long that alternatives are not obvious.

Giving due credit, Rothman appreciates that the “foodies have taught us how to think about our food.” That is really the quarry. Not just changing who attends births and where they happen, but how ordinary people think about the whole thing. The way you think about your little bowl of cereal can engage the whole globe. The way you proceed in the hour of birth rests on the rest of life, just as our understanding of a good death hangs with the whole tissue of a life. The connection allows Rothman to demand, “Can it possibly be right that almost every baby begins life in precisely the place almost every older person passionately wants not to end it?” What is at stake in the way births occur, to allow one of Rothman’s chapter titles to draw near the final word, is “Living the Embodied Life.” I don’t think it should be all that hard to persuade people to care how they, personally, came to be, and how the species at large keeps on doing it.

Agnes Howard teaches at Christ College, the honors college of Valparaiso University. Her writing has appeared in Commonweal, First Things, and other publications.