These days there seems to be a greater sense that grief, whether experienced for the loss of an intimate or for the loss of one’s own vitality, is a private affair that no one but those directly affected can know. Pain and suffering reduce the distance that separates human beings from each other, but they just as often reinforce our differences, pushing the individual toward isolation. What grief means, and where one stands in relation to the concentric circles that ripple outward from the ache of a particular loss, is fraught with uncertainty. We are too quick to console, or perhaps we say the wrong thing. When we are the ones in pain and the roles are reversed, we can be too quick to reject consolation. It is ludicrous to hear that our suffering is somehow the result of God’s plan. No wonder so many readers seek the counsel of the afflicted in these matters.

After witnessing a friend’s battle with colon cancer, I gravitated toward the first-person accounts of illness in J. Todd Billings’s Rejoicing in Lament (2015) and Paul Kalanithi’s best-selling When Breath Becomes Air (2016). Such testimonies help make loss livable, granting readers access to the personal experience of suffering while preserving it as a form of private property, unique to the witness of the individual telling the story.

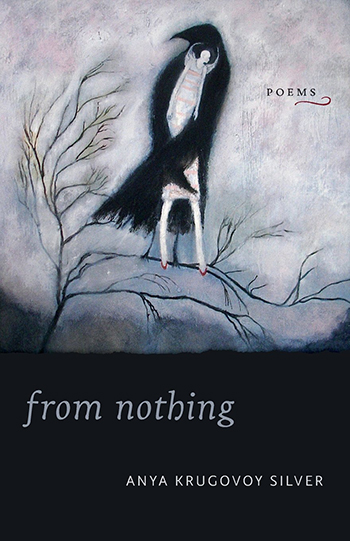

As a survivor of breast cancer, Anya Krugovoy Silver is a

capable guide in matters of grief and loss. Her second collection of poetry, From

Nothing (LSU), reflects on the experience of living through illness while

attempting to embrace the fullness of both motherhood and mortality. In these

poems, bracing honesty coincides with the quiet transformations of language.

Especially moving are the expressions of praise that take shape in the absence

of consolation. In a 2011 pamphlet, pastor John Piper exhorted Christians not

to “waste” their illness. He urged that we look for “[t]he design of God in our

cancer.” As Silver makes clear, there is a great distance separating the pastor

from the poet, and much to learn in turning from moral instruction to the

burdensome journeys of the body.

As a survivor of breast cancer, Anya Krugovoy Silver is a

capable guide in matters of grief and loss. Her second collection of poetry, From

Nothing (LSU), reflects on the experience of living through illness while

attempting to embrace the fullness of both motherhood and mortality. In these

poems, bracing honesty coincides with the quiet transformations of language.

Especially moving are the expressions of praise that take shape in the absence

of consolation. In a 2011 pamphlet, pastor John Piper exhorted Christians not

to “waste” their illness. He urged that we look for “[t]he design of God in our

cancer.” As Silver makes clear, there is a great distance separating the pastor

from the poet, and much to learn in turning from moral instruction to the

burdensome journeys of the body.

Silver’s poems explore the facts of being acted upon, plumbing the experience of weakness that results from severe illness. An example is the poem “Poise,” which begins by comparing the poet to the perfect balance of “The little ballerina in my cardboard jewelry box.” The small figurine only serves to point up the stark differences between ballerina and cancer patient. What characterizes Silver’s experience of illness is not “poise” but, “rather, that I am posed.” The patient is forced to confront her lack of control at the level of the multiplying cells that ravage her body. She feels like an automaton in her regimen of treatments, stating “I perform cancer.” As an actor, she cannot resist the role that she must play. In “How to Unwant What the Body Has Wanted,” Silver gives herself a set of instructions, in the hope that self-discipline may perhaps recover a measure of freedom. The instructions include such advice as “Confuse the body with sugar until the sugar tastes like love.” “Take root,” she tells herself. “Let the web of branches hold you.” Especially resonant is the one-line command, “Sleep as deeply alive as an acorn in your bed’s black earth.” The acorn stands out as a complex image of burial and birth in this rhythmic line. It suggests how the cancer patient holds within herself, even when undergoing treatment, the potential of one day returning to the open air.

The hope of return and restoration is carried forward in “Kore,” a poem from the last of the book’s three sections. The poem’s title refers to the goddess Persephone, who according to myth was abducted by Hades, the god of the underworld, and only permitted to return to earth for the seasons of spring and summer. The poem serves as an allegory of the patient’s escape from the privations of treatment. In particular, the description of return suggests the end of chemotherapy, as in the lines “Instantly, her shorn head comes alive, curls / forcing themselves through her bald skull.” The patient returns to the luxuriance of the body. The image of return takes even more sensuous form in “Wisteria,” where Silver describes a woman who, being “forty-five / and disfigured,” rues the loss of physical intimacy: “She hadn’t wanted to let it go, had wrenched hard / to keep it, had wept, gone stiff and angry.” The poem recounts the surprise when, “suddenly, he was back, the bark / she had traced so wistfully bearing blossom.” The shift from loss to indulgent joy is overpowering:

Wisteria hung opulent from the wire fence, papery petals sweating sugar. Yes, she had it again.Temporary, but no matter. It had returned to her. She forgot how to speak: she crammed; she raved.

This portrayal of the reawakened body is striking, the depiction of sexual vigor gorgeously rendered.

Silver’s poems struggle with the problematic nature of speaking for others. An example is “Tenebrae,” which refers to the church service during Holy Week in which candles are gradually extinguished to leave the church in a pall of silence. The service commemorates the darkness of Christ’s journey toward the Cross. The title is fitting for the subject matter of the poem. The service enacts the confusion and sorrow that result from serving as a witness to suffering. In several poems, Silver inhabits a liminal state where consolation is distant or uncertain. The choice of Holy Week, and the liturgical tradition in particular, offers a ritual framework that gives expression to the experience of pain. If, as countless sermons have told us, God uses suffering to bring us closer to him, Silver suggests how trite such words can sound. As if in response to those who have offered spiritual consolation, the poem opens with a prayer for a fellow cancer-sufferer who has recently entered hospice:

Lord, I know the bitterness is for

her own good.

Through the numbness that has made her quadriplegic,

she has drawn nearer to you, has been purged

as with bloodroot of whatever sins still grieved you.

This opening strikes a curious tone. The assertion of “I know” suggests the distance that separates doctrinal knowledge from lived experience. It is the same distance that separates the outside observer from the sufferer. The poet begins by taking the perspective of the one who knows better or who sees more clearly what God is doing in another person’s life—in order to show readers the hollowness of such words. Whatever is “for her own good” is something the patient would not willingly choose. The illness has stripped the woman of her will.

As these lines sink in, the reader begins to recoil from them. Something like this happens, for instance, with the scriptural echo of the “gall of bitterness,” from Acts 8:23 (KJV), in the first line. The echo suggests our tendency to spiritualize the experience of brute pain, to look for a divine purpose in a complex series of unthinking secondary causes. In the opening of this poem, it is important that the sentence stops at the end of the first line. The coincidence of syntax and line gives the appearance of a self-contained unit, as if complete in itself, as if one had all the knowledge one needed. The fact that the poem continues belies the pretense of certainty.

From this description of “Tenebrae,” one of the most wrenching poems in the volume, it might sound like the poet is angry with God, or at least with Christian culture, bent on critiquing the pat explanations given in response to questions arising from misfortune. But Silver’s poems do not mock. They question and confess, but they are not laced with gall. She writes in “Tenebrae,” “Thank you, God, for your wisdom that widows, / For the orphans who continue to praise you.” The “wisdom that widows” is a crushing phrase, yet we are called to recognize, rather than discount, the hosannas of the orphan. Although the tone here is complex, I do not read Silver’s expression of gratitude as ironic. Silver quietly accepts that wisdom does indeed issue from suffering. She is unwilling to discount the experience of those who make such claims based on personal experience. Illness does, in many instances, draw a person closer to God. But such wisdom is not what she yearns for. The demands of empathy require her to affirm the voice of the orphan, and yet the poem suggests that there is something distasteful, perhaps unethical, about claiming suffering’s wisdom on behalf of the voiceless. To claim such wisdom for the friend in hospice is inappropriate. The ending of the poem refuses to draw a moral lesson. While her friend “sleeps her morphine dreams,” the poet pleads to God: “spare me your will and secret knowledge. / Let me continue to live, ignorant and erring.” At this point in the book, the reader knows full well about Silver’s cancer. The ending unfolds not with defiance but with a hint of the spirit’s exhaustion.

It is a mystery, when one is ill, that life for others continues to hold blessings of deep joy. It becomes difficult to keep the wisdom of mortality from extending its blight to others. The poem “Coincidence” wrestles with this mystery as it recounts a post-mastectomy visit to the doctor: “The same morning I press my shorn chest / against an X-ray machine and hold my breath, / my sister births from her body a baby girl.” The occasion becomes a reminder of absence, with the “shorn chest” serving as a stark contrast to “the nursing whole breast” of her sister. What follows is an act of praise that is more the result of disciplined practice than spontaneous expression—but which is no less valuable for that. The X-ray becomes a metaphorical hinge that unites the two life experiences:

Praise God, whose hands pass over each other

like river currents as they give and take,

pulling one film from the whirring machine

while pushing in a new, unprinted slide.

The reader does not take this praise for granted, because Silver continually attempts to grasp the “fearful doubling” of joy and pain that consists of life in the present. “Coincidence” ends in restrained wonder, offering a description without a verb. Silver imagines “Little breathing at the nursing whole breast / of my sister, little gold seed of death / awakening as the first sun touches its tendrils.” The organic metaphor demonstrates the refusal to turn away from the brute facts of mortality that one often finds in this collection. The bright newness of the infant is an occasion for praise even as we are reminded that the child contains within it the beginning of its end. Silver may not offer the celebratory exclamations that are customary in such circumstances, but she has seen too much to content herself, or her loved ones, with platitudes. Her voice, like her body, bears the scars of her experience.

The phrase from nothing recalls the theological doctrine of creation ex nihilo. As a broken or partial phrase, Silver’s title points to the uncertainty that follows loss. What assurance do we have that beauty can be wrought from the void of suffering? How can the activity of making follow from the experience of being on the verge of nothingness? In the midst of grief, this moving collection attests to the strength and persistence of Silver’s voice. An image of her will to endure appears in “The Raven.” In the dreamscape of that poem, Silver imagines how the huge black bird, after carrying her through the night, “set me gently / down in my home, among the sleepers, / and dawn drove a pen into my hand.”

Jeffrey Galbraith is assistant professor of English at Wheaton College.